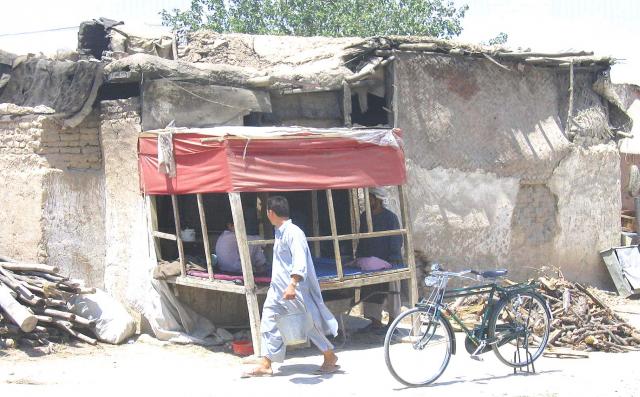

Urban Livelihoods in Afghanistan (Jo Beall)

Two major studies led by Jo Beall for the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU)1 were among the first to highlight the unprecedented and largely unplanned urbanisation that now characterises the country, as well as the realities of urban poverty and vulnerability for growing numbers of Afghans. Together the reports draw on two years of research conducted in Kabul, Heart, Jalalabad, Mazar-i-Sharif and Pul-i-Khumri, with the second study tracking the life paths of poor urban households over an entire year.

|

Afghanistan’s urban poor have little or no access to basic services and social infrastructure, with polluted water and poor sanitation contributing to chronic health problems that compromise their ability to earn a living. They are also vulnerable. Many have lost loved ones and breadwinners and have been displaced by violent conflict. Their material asset base has been depleted and their social networks dislocated. Livelihoods are mainly pursued by way of insecure informal employment, characterised by erratic incomes and high seasonality. Women significantly contribute to household incomes, with home-based work being the third largest employment category overall. Although many schools are being built in the wake of war, poor households have to put their children to work, often in exploitative and hazardous occupations. Irregular income flows lead many households to rely on borrowing, the result being that a great majority are in constant debt. All this is in a context of high prices, rising rents and where competition for accommodation is rendered dangerous by contested ownership and land grabbing.

Yet the plight of the urban poor is largely neglected by municipalities and national government departments who either lack the capacity, resources and political will to address it and who remain wedded to master plans developed in the 1970s that bear no relation to Afghanistan’s contemporary urban reality. Above all a path needs to be negotiated between the rigidity of formal master planning and the reality of burgeoning informality, including the recognition and legalisation of informal settlements. This needs to be accompanied by appreciation of the contribution of informal economic activities, alongside broad-based labour intensive growth and social protection strategies, executed at both the national and city level, and in a context that redresses the imbalance caused by a predominantly rural focus in national reconstruction and development assistance.

|

- ________________

1 The first report (2005), funded by the World Bank, was on urban issues and can be accessed in full via the following link:

http://www.lse.ac.uk/collections/DESTIN/pdf/AREU%20Urban%20Livelihoods%20SP%20FINAL%20PROOF%205Oct2006.pdf

The second report (2006) on urban livelihoods was funded by the European Union and can be found at:

http://www.areu.org.af/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=30&Itemid=35