Neighbourhood Planning in Kabul’s old city (Anna Soave)

Submitted by frankie on Fri, 2009-04-10 11:15.

Anna Soave

The views expressed in 'Recent News & Reflections' are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of any of the governments, organisations or agencies with whom they have been working.

Seconded in 2003 by the DPU to the Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Historic Cities Programme (AKTC/HCP), Anna Soave has been working in Kabul for 5 years as an urban planner engaged in hands-on planning in the low-income and war-affected areas of the Old City, in support of AKTC’s on-going rehabilitation programme in Afghanistan.

|

|

Once a prosperous trading, manufacturing and residential area, the centre of Kabul has suffered from progressive decline since the 1920s, when its wealthier families moved to the new leafy suburbs of Share Nau, north of the river, and Darulaman towards the south. Although crowded and notoriously insalubrious, the old city maintained its commercial role and continued to attract trade and merchants to its bustling bazaars. Significant public investments were made in the 1950s to improve its connectivity and representational character, including the Haussman-style opening of Jade Maiwand. Had it not been for the later political upheaval, the dense historic fabric and crooked streets would have in all likelihood have been gradually replaced by the high-rise apartments blocks, grand administration buildings and wide roads envisaged by the Soviet-inspired 1978 Master Plan – in line with the contemporary modernist ideals. Most of this fabric was in fact lost in 1992/93 during the inter-factional conflict that affected much of the old city and Kabul’s southern neighbourhoods of Karte Seh and Darulaman. After 2001, with the rapid influx of refugees and internally displaced people settling in the capital, the pace of spontaneous reconstruction quickened. As demand for housing, infrastructure and services grew at unprecedented levels, and foreign donors prioritised other development sectors, Afghan professionals and the authorities faced an urban crisis for which they were ill-prepared. While urban officials spent years debating between the legitimacy of the Soviet-influenced Master Plan and the need for a newly-drafted plan for the capital, the city was developing unchecked. Thus it is not surprising that despite the urgency of intervention, the historic quarters, with an estimated current population of 55-60.000 people, remain marginal to the wider process of urban development and conservation issues are yet to be addressed in official policy. In spite of the official ban on new construction imposed in 2002, in an effort to prevent the destruction of what little historic structures had survived, a number of multi-storey commercial buildings were constructed with impunity along the main commercial roads and several neighbourhoods gradually reverted to their traditional self-built settlement pattern, with many historic structures being demolished on a daily basis. In an effort to protect what was left of its historic cities, the Ministry of Urban Development (MoUD) established in 2004 a Department for the Safeguarding Afghanistan’s Urban Heritage (DSAUH). Tasked to prepare a comprehensive development plan for the historic quarters of all major Afghan cities, the newly-established Department struggled to develop sufficient technical capacity and to assert its authority in a context beset by weak institutions with competing mandates. This situation is exacerbated by the absence of a coherent national urban policy, as well as the adequate legal instruments to protect urban heritage.

|

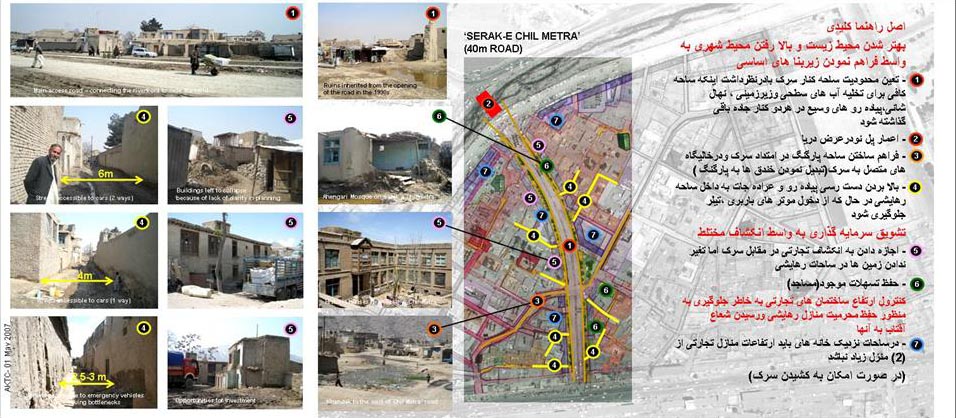

Initiated in 2002, by 2008 the AKTC’s programme has included the restoration of significant cultural landmarks, such as the 16th-century Babur Gardens reclining on the southern slopes of the Asmayee mountain and the Timur Shah Mausoleum overlooking the River Kabul, as well as an extensive project of rehabilitation of the historic quarters of Asheqan wa Arefan, Chindawol and Kharabat, and the reconstruction of key public buildings in Pakhta Furushi, Shane Sazi and Tandoor Sazi at the heart of the Old City. Since the inception of its programme, AKTC aimed at developing an integrated approach for the physical rehabilitation of key historic public buildings, such as mosques, shrines, hammams, and a madrasa, and interventions on private houses deemed in danger, in parallel to an ambitious plan for access upgrading, environmental improvements and enhancement of public spaces. In an attempt to contribute to a wider effort of rehabilitation of the area, the project included the provision of a growing number of small-scale grants to property owners for repairs to their traditional homes, in the form of construction materials, equipment, skilled labour and technical supervision. A substantial program component was also represented by employment generation and on-the-job craftsmanship training for workers employed from the historic quarters, as well as on site training of recently-graduated architects and site supervisors.

Within the aim of supporting the on-going rehabilitation program, Anna was essentially tasked to contribute to the drafting of an appropriate planning framework for the Old City of Kabul; engage in the development of technical capacity amongst Afghan urban professionals, both within AKTC and among partner organisations such as DSAUH; liaise with counterparts; and develop advocacy and awareness-raising material. Admittedly, getting involved in urban rehabilitation in Kabul is not for the faint-hearted. The complexities of the current political, social and economic situation of the country, coupled with the existing planning needs for the regeneration of its capital city, require for a start a humble review of ones’ capacity, professional knowledge and presumptions. The particular conditions of the historic quarters represent an additional and challenging dimension, with its legacy of social marginalisation, dilapidated housing stock, under-investments in infrastructure, traffic congestion, environmental degradation, number of absentee owners and property disputes.

Thus, in the context of two decades of planning vacuum, obsolete cadastral maps, lack of updated census figures and uncontrolled development, Anna and a small team of young Afghan professionals undertook an analysis of the areas of concern, based upon physical and socio-economic surveying, street-by-street mapping and documentation – prior to any planning work. This process required a significant effort in the consultation of community representatives and local authorities, with whom the resulting documentation has been regularly shared in an effort to bridge between the different realities and perceptions. Following the drafting of a set of building guidelines based upon local customary laws, in 2004/5 the team submitted a planning framework to MoUD to guide the development of the residential area of Chindawol. Since the failure of the authorities to endorse either document, the team opted for a more direct approach, engaging DSAUH engineers in joint site surveys, mapping activities and drafting of neighbourhood plans during weekly planning workshops in their ministerial offices. This process has been a mixture of achievements and disappointments, as priorities within the Department often shifted, leaderships changed, pressure mounted and staff struggled to meet deadlines. Having failed to produce the required plans, DSAUH effectively held hostage the overall redevelopment process for years.

|

|

Throughout this teamwork, the team has been actively seeking to promote “hands-on” urban planning as a practice that needs to reflect the reality in its complexity, encompassing economic, political, physical and social conditions to be dealt with concurrently. It focused on defining appropriate planning approaches in order to develop realistic strategies for the conservation of historic buildings and the upgrading of surrounding fabric based upon the engagement of local stakeholders in their physical recovery. This has often meant fighting the reluctance of local authorities to acknowledge the value of self-reliance of urban dwellers, and to recognize the obsolescence of planning tools inherited from the 1970s, in order to draft effective urban strategies and thus ‘fast-forward’ development in a reality of urgent needs and high expectations.

Despite the challenges, AKTC managed to build meaningful partnerships with the DSAUH team and the Department of Historic Monuments (MoHM) of the Ministry of Information & Culture (MoIC), as well as with the district office of the Kabul Municipality. As part of its efforts to improve coordination between the various institutions active in the old city, the AKTC planning team has also provided regular survey findings and planning material to the Kabul Old City Commission (KOCC), the inter-institutional platform established by MoUD in 2006, and tasked to oversee and coordinate initiatives in the historic quarters.

In the context of the World Bank-funded Kabul Urban Reconstruction Project (KURP), AKTC was specifically tasked in 2008 to produce a series of action plans for the authorities involved in the Old City and the development of optimal procedures for urban upgrading in historic areas. The assignment also included an action plan for the drafting of a much needed national urban heritage policy. Maintaining this momentum will be crucial. Yet, for these processes to create the adequate synergies it will take time – and time is today a resource in short supply. The window of opportunity that urban decision-makers and development agencies had until recently is rapidly closing. Could it already be too late to safeguard what remains of the historic fabric of the old city and to deter the risk of socio-economic decline of the core of the city? With ad hoc and insensitive reconstruction rapidly transforming these fragile historic areas, it is still essential to set up effective planning and regulatory processes – let alone meet the needs of its growing population.

Web links:

Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Historic Cities Programme: http://www.akdn.org/aktc

AKTC Newsletters: http://www.akdn.org/afghanistan_newsletters.asp

Aga Khan Historic Cities Programme, Urban Conservation and Area Development in Afghanistan, AKTC, Geneva, 2007: http://www.akdn.org/publications/akhcp_afghanistan.pdf

ArchNet Digital Library: http://www.archnet.org/library/