Urban Issues in Pakistan: Interview (Babar Mumtaz)

Submitted by frankie on Sat, 2021-01-09 11:34.

Babar Mumtaz

The views expressed in 'Recent News & Reflections' are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of any of the governments, organisations or agencies with whom they have been working.

Reproduced from ‘Pakistan Institute of Development Economics: Cities and Urbanisation, P&R Issue, Interviews', Jan. 2021

Babar Khan Mumtaz

is an economist and architect, formerly Director of the DPU, University College London. He has worked for governments and international agencies in Africa, Middle East, South Asia and the South Pacific for over 45 years.

Q. In your opinion, are there commonalities when it comes to planning issues that afflict cities in high income Global North countries and low- & middle-income countries of the Global South?

A. It goes without saying that yes, there are commonalities, and indeed, always will be, regardless of the size of the city, it’s economy or its social composition. Furthermore, regardless of the de- tail, the “problem” for urban planners everywhere is essentially one of how to provide appropriate accommodation, mobility, employment and enjoyment within the available resources. People are not easily satisfied - and indeed our economic paradigm requires that they are not - so it is a continuous struggle. Drastic and dramatic events, natural calamities, wars and pandemics tend to create opportunities for change, precisely because they disrupt the status quo, and allow for some re-examination of assumptions of where are we going but also a questioning of how we are doing so.

The need to plan is a basic human trait - and one that allowed mankind to dominate all the other species despite our physical limitations. Integrated and underlying all of the religious texts are guidelines for social and societal behaviour - but they all belong to an earlier phase of our existence when we were transiting from a hunter-gathering state to a settled agricultural economy. All of the religious texts are built on rural references and imagery...of flocks and lambs and shepherds in their huts (and of course, the kings in their palaces). Islam, I think, was the first and perhaps only urban religion, built on trade, exchange and interchange (the gardens are for the life hereafter).

The planning of cities consisted of apportioning sections on the basis of tribe or vocation, with bazars along the streets that ran between them. The planning of the space in-between was based on 2 principles: it must be possible to reach each household with a street wide and routed such as to allow the transport of funeral cortege, and secondly, that any water reaching a plot must be al- lowed to flow freely across it and to the other side unimpeded.

This served well until the industrial revolution separated work and workers, and later, the auto- mobile drove out the people out of the city and introduced commuting. Now, as we enter the 5th Industrial Revolution, where geography is history, we could be on the cusp of a post-Corona end of the city as the dominant feature of our landscape. Instead of the dominant urban problem being mobility and employment our focus may be accommodation and enjoyment.

|

Q. Urban areas in Pakistan are facing uncontrolled urban sprawl. From you experience and understanding what are prime causes of this sprawl and what could be examples of some useful policy interventions?

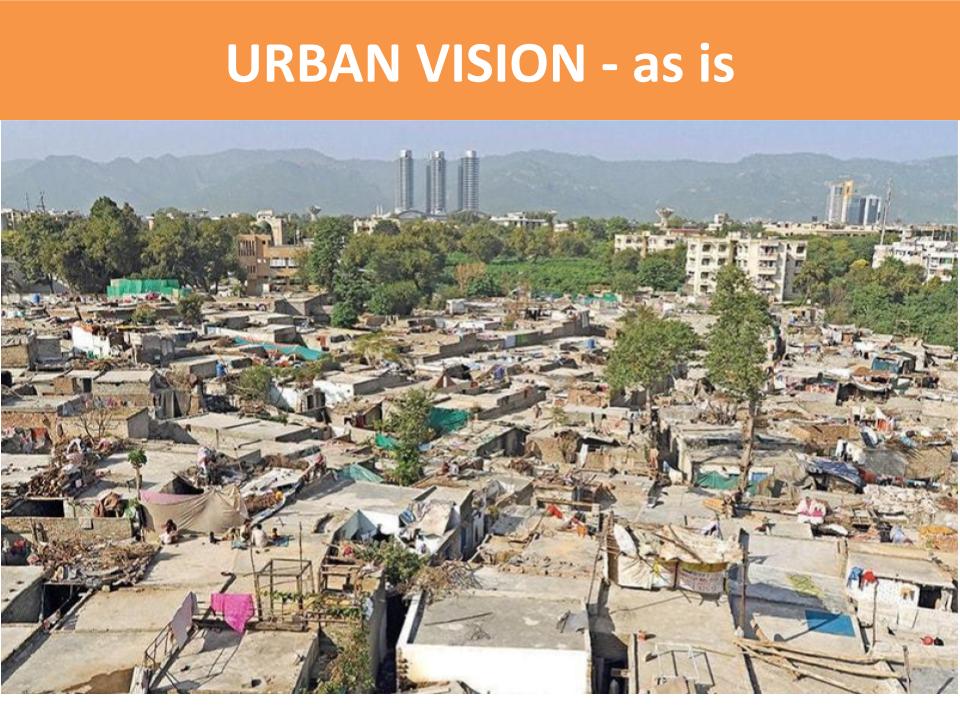

A. There are a number of reasons why we have urban sprawl, but to my mind, we can lay the blame on urban planning. It is not that urban planners produced plans that promoted or advocated or even facilitated urban sprawl so much as that there has been very little urban planning. That is not to say that urban plans have not been commissioned so much as that they have not been practiced. There seems to be reluctance amongst both our bureaucrats and our decision-takers (both civil and military) to not want to have their hands tied by planning and thus limiting their room for manoeuvre. We are also reluctant to delegate decision-making. The result is that our plans are often left to play catch-up. We all know that the size of our cities will double over the next 10-15 years, but have no idea how or where this population will be housed. Those who take decisions are the ones who make them. The city is defined by the development of colonies for the defence and the bureaucrats. It is this that is responsible for urban sprawl.

In Lahore, in 2012, according to the Urban Unit, the poorest 50% of the population was living on 10% of the land while the richer 10% was living on 50% of the total area.

A moratorium on development of (or on) new land, coupled with the right to develop all land up to 4 stories, subject to structural confirmation and the payment of development changes (which will be used to expand or lay additional sewer, water and gas lines), would increase densities and accommodate future population growth with the need for developing new land or extending the built-up area of cities.

Virtually all houses have been built without re- course to formal housing finance: only 2% of Pakistani houses have any formal housing loans. There is no house in Pakistan that has been built using formal housing finance only. So “Housing Finance” and “Affordability” is not the problem. The reason that some areas of cities are “slums” and “unacceptable” (some UN estimates put this figure at 55% of all housing) is not because of the actions of the households so much as the lack of action by urban authorities: 3 of the 5 criteria that define slums are to do with urban services, the other 2 arise from insecurity of tenure. Katchiabadis are not formed by newcomers or migrants – knowledge of the land market and police and political protection is needed to initiate settlements (Arif Hasan has documented this extensively) – nor are rural migrants attracted by “housing” – that is about the only thing they already have. What they come to the cities for are jobs and services.

|

Q. The incumbent government used the slogan of ‘providing affordable housing options’ for the poor during its election campaign. On a practical front, do you think it is possible for a country like Pakistan to execute such a promise given the lack of public funds and the extremely high land and construction costs?

A. Every government in Pakistan has promised to “solve” the housing problem, whether by the Prime Minister’s Housing Scheme, the 7 marla housing, the 5 marla housing scheme or the mil- lion houses programme.

None have delivered, many have not actually built any houses at all, and even those that have been heavily subsidized and not gone to the right people. The only beneficiaries of the schemes have been the property developers who have been al- located public land.

The reality of housing in Pakistan is that according to PSLM 2018-19, over 84% of all Pakistanis (91% in rural areas) own their houses and another 5% live in free housing. Over two-thirds have 2 rooms or more. So there is no huge “shortage” of houses; there is no yawning “housing gap”.

96% of the urban houses (70% of rural houses), have brick walls and rcc roofs. So, there are very few “katcha houses”. The abadis are called Katchi because they are not legally sanctioned settlements.

Virtually all houses have been built without recourse to formal housing finance: only 2% of Pakistani houses have any formal housing loans. There is no house in Pakistan that has been built using formal housing finance only. So “Housing Finance” and “Affordability” is not the problem. The reason that some areas of cities are “slums” and “unacceptable” (some UN estimates put this figure at 55% of all housing) is not because of the actions of the households so much as the lack of action by urban authorities: 3 of the 5 criteria that define slums are to do with urban services, the other 2 arise from insecurity of tenure. Katchi abadis are not formed by newcomers or migrants – knowledge of the land market and police and political protection is needed to initiate settlements (Arif Hasan has documented this extensively) – nor are rural migrants attracted by “housing” – that is about the only thing they already have. What they come to the cities for are jobs and services.

The “Housing Problem” in Pakistan, and especially in Pakistan’s cities consists of quality and not quantity. Moreover, the “quality gap” is most likely caused not so much by finance or capability or willingness on the part of the households as it is of the legal frameworks and their application.

As for whether the government of a poor country “solving the housing problem”, of course it can, but not by building houses. Instead of transfer- ring public land to developers, give tenurial rights to the squatters on public land (create group ownership), provide urban services to these settlements. Allocate land within upper income housing schemes. The poorest 20% of the population uses only 4% of the land.

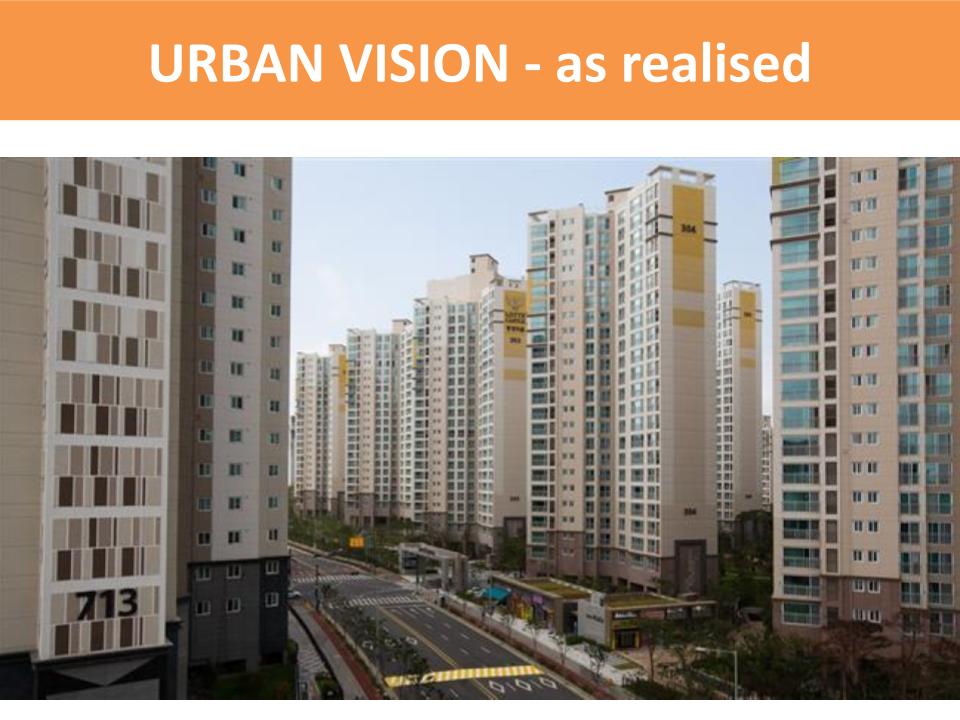

Q. Why do you feel high-rise development and mixed-use of urban land has not gained much traction with successive governments and its policymakers in Pakistan?

A. Partly the reason is the same as for urban sprawl, and this is further reinforced by the presumption that the “bungalow” is a sign of status and wealth. Consequently, legislation does not allow high-rise. As long as flats are only restricted to the middle classes, high-rise will not happen. As for mixed development, that too is enshrined in the legislation, but in practice, there is a lot of mixed use, ranging from schools, clinics etc. to offices and gyms and restaurants.

|

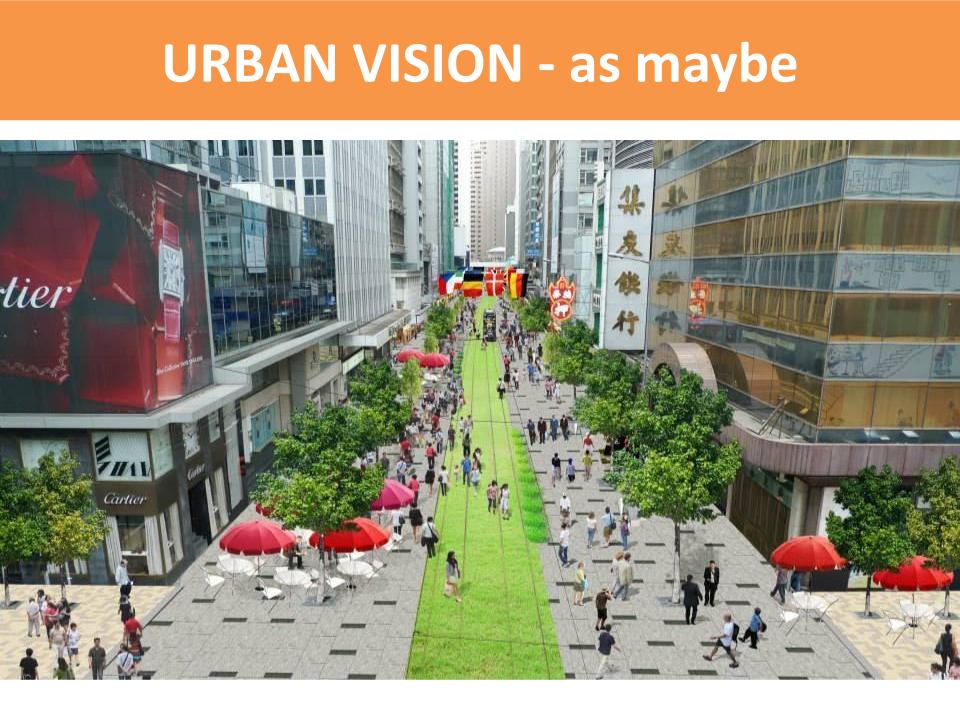

Q. From your experience or otherwise, can you share an example of a country/city that successfully transformed its urban landscape?

A. Gent, in Belgium, is a vivid, vibrant, and growing city. This has plenty of advantages, but also brings with it some challenges, as the pressure of motorized traffic on the city keeps on growing. To ensure Ghent’s accessibility and livability in the future, the city council decided to implement a new Circulation Plan in April 2017.

Whoever now wants to move from one city district to another must make use of the inner-city ring road. The ultimate goal of the Circulation Plan is to take through traffic out of the city centre. That means whoever needs to be in the city centre will be able to get there more easily.

Car usage reduced from 55 to 27 per cent;

Cycling increasing from 22 to 30 per cent;

Public transport usage increasing from 9 to 20 per cent;

Walking increasing from 15 to 18 per cent.

In Eskisehir, Turkey, congestion was clogging the city center, and the central Porsuk River became one of the region’s most polluted bodies of water. To combat these issues, the Eskisehir Metropolitan Municipality created a network of natural infrastructure to restore the Porsuk, expand public green spaces and link the entire corridor with a sustainable public transport network.

The Eskisehir Urban Development Project interweaves green and grey infrastructure with a new electric tram network to create a modern, nature-based city. Parks along the river have helped improve water quality and control flooding, while also spurring new commercial growth and pedestrian traffic.

Since the project launched, green space per city resident has increased 215 percent, 24 miles of electric tram lines move more than 130,000 people per day, and the city has become a hub for domestic and international tourism.

|

Q. According to recent estimates about half of Pakistan is urbanized. Given this, why do you think the myth of Pakistan being predominantly a ‘rural country’ still persists in certain policy circles? (Conventionally urban located sectors of services and industry account for over 75% of GDP).

A. On the one hand, traditionally, political power was more firmly entrenched with the feudal families, and they were able to deliver votes more consistently, whereas urban voters were far more fickle and less reliable.

Their hold over budget allocations was therefore firmer. On the other hand, there persists the “arcadian dream” amongst the aid community who transfer their biases to aid programmes and would like to reverse rural-urban migration and indeed “modernisation”. This was also responsible for the “urban bias” myth and it was used to divert flows to the rural areas.

The combination has been hard to beat.